Understanding how your workforce learns can make them more productive

Organizations who master teaching in a way that matches their employees’ learning process will prosper.

- Fewer employees are doing more work, but the tools they use and the work they do have become much more complicated.

- Many systems offered as “solutions” have only exacerbated the problem further by introducing more complexity.

- By understanding the mechanics of how your work force learns, you can provide training that sticks.

- From the beginning, the fundamental nature of how the brain learns has served as the compass for developing the Acadia Performance Platform.

Investments in new technology are leaving companies with less to invest in training and development while their dependence on individual employees is growing sharply. Workers are being asked to achieve more productivity with less resources while their jobs are becoming more complex, eroding the competitive marketplace advantage of their employers. To facilitate productivity, engagement and retention, we need to reconsider how we train and equip our team members. Organizations who master teaching in a way that matches their employees’ learning process will prosper.

Why employee learning is so important

Work in the last several decades has become increasingly complex. Mass-digitization of information, decreasing costs of computation, and ease of communication across the organization have all contributed to major changes in the way we work.1 With each technological breakthrough, companies have been able to become more productive with less human capital.

These advances come with their own costs. While less employees are doing more work, the tools they use and the work they do has become much more complicated. According to Deloitte, more than 80% of organizations recognize the need to simplify work as an important problem.2 Ignoring this problem leads to even bigger issues with employee productivity, engagement3 and ultimately retention.4

Why the most prominent solutions aren’t paying off

To address the issue of complexity, a multi-billion-dollar industry has emerged to facilitate the way we train our employees and share knowledge across our organizations. Unfortunately, many of these solutions have only exacerbated the problem further by introducing more complexity.

Management systems provide tools for developing and organizing training materials, but not a framework for driving employee engagement in their day-to-day work. They require large upfront investments in budget, IT and infrastructure. They don’t integrate easily with existing HR or Business Management systems. And while they do help to produce and organize content, they don’t help to identify the best content, or determine who should be viewing it, or provide it to you when you need it.

So, what’s missing from these systems? Many of them focus on the act of training, organizing files and tracking their use. They don’t reinforce best practices, help to identify better ones, or become a part of the workflow itself. Most importantly they don’t focus on the way people learn, or how to change behavior.

If standardizing and training on the performance of complex procedures is important to your business, first you need to understand the basics of how your employees process information into knowledge.

How the brain sorts inbound data

New information is introduced to us through our senses. Data enters our brain at a dizzying pace. Take a moment to try to notice all the external forces impacting your current environment.

What sounds can you hear? What do you see as you look around? What’s the temperature? What can you smell?

The number of competing inputs will vary greatly depending on your location.

Is the phone ringing? Is your co-worker talking on the other side of the wall? Is your calendar alert popping up? Are your kids playing with the dog? Is your spouse making dinner?

Your brain takes in every single one of the hundreds and thousands of signals around you. Thankfully, you don’t have to think about each of these signals individually and decide how to react to them.

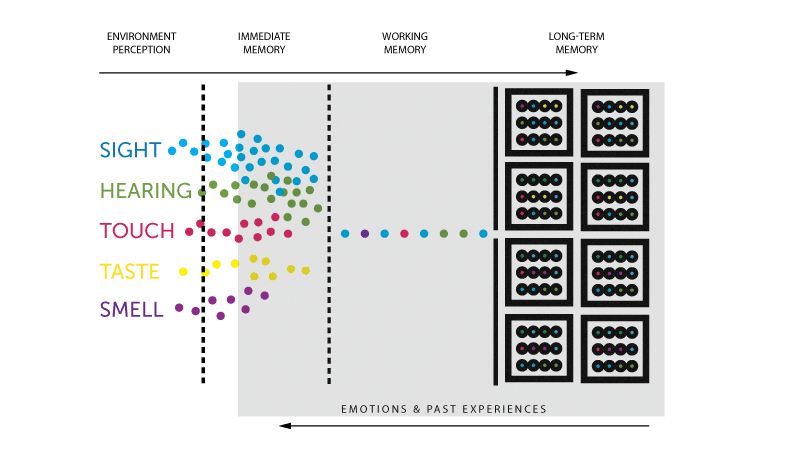

As information comes into your brain through your senses, it enters your immediate memory. Here, your brain makes quick (millisecond) judgements – based on previous experiences – about whether to further review the information or discard it.

For example, if you see an ambulance coming with lights and sirens, you immediately take notice. You assess the situation and decide what to do based on previous experience. But if a colleague’s phone rings, you probably don’t even hear it.

Once the brain discards something, it’s gone for good.6 However, if based upon previous experiences, your brain decides that certain information requires additional attention, it is passed along to your working memory.

In your working memory, your brain must make a lot of decisions, so it can only process a few things at a time. Your working memory determines whether a piece of information is:

- something to simply discard – a passing smell that reminded you of your grandmother

- something that you should maintain for a short period – where did you park at the grocery store

- something that is compelling enough to make a permanent part of you – August 23 is your son’s birthday.

Which memories become part of you

Every new input that your brain processes is filtered through your past experiences. The information the brain readily passes into long-term memory relates to survival, or your most vivid emotions. So typically, the best and worst things that happen to you become long-term memories fastest and easiest.

For most of us, the best and worst moments of our lives don’t happen, on a regular basis, during our work life. Fortunately, the brain has another standard for entering information into long-term memory. The other process performed on information in working memory is an assessment of whether the information makes sense and whether it has meaning.6 If information makes sense, that means it fits into the way you understand the world. If information has meaning that means it is relevant to you.

Learning in the workplace

When information is presented to you during the work day, you review it in context of what you understand about your job, your company and your industry. If the information fits into that context, it will likely have meaning for you. If you can envision it applying to your personal work, then it is relevant for you. With both boxes checked, the information is a candidate for long-term memory storage.

However, experience always shades how new information is perceived too. If an employee has had a previous experience with something and it didn’t work, they will likely expect new, similar information to perform the same way.6

For example, imagine an employee was attempting to locate an SOP document on Sharepoint and couldn’t find it after several attempts. That negative experience could taint their view of any document on that platform. Now when you reference a new document, you not only have to rely on the quality of the document itself, you must also overcome the prior negative experience.

Another important aspect of learning is repetition or practice. Activities performed at work are really no different than riding a bike or playing a musical instrument. As you practice an activity, you become more efficient at it. When the same information is presented to your brain with repetition, it begins to develop physical and chemical changes that relate to the activity. Eventually, the activity can be performed reflexively as the brain builds a pattern that is automatically recalled when you perform the task.

That’s why it’s critical that materials used in training are also incorporated into daily activity. While in-person training sessions are valuable at introducing the information into the working memory, the brain will only retain certain portions of that information, and only for a short period of time. If the pattern of information is repeated while it is still in working memory, then it is much more likely that it will pass into long-term memory.

The trick is making sure that the same materials are used throughout the learning process and well into the performance of the task.

Keys to helping employees learn:

- Make the information meaningful and relevant.

- Present it in a clear and actionable manner, leaving the employee with the expectation that this will help them succeed.

- Engage as many senses as possible with the material.

- Give them the information in context, ideally while they are performing the task.

- Make the information part of the task so that it is repeated each time and the employee knows s/he is responsible for it.

- Check for comprehension to ensure the most important information has been retained.

Tools built on these principles

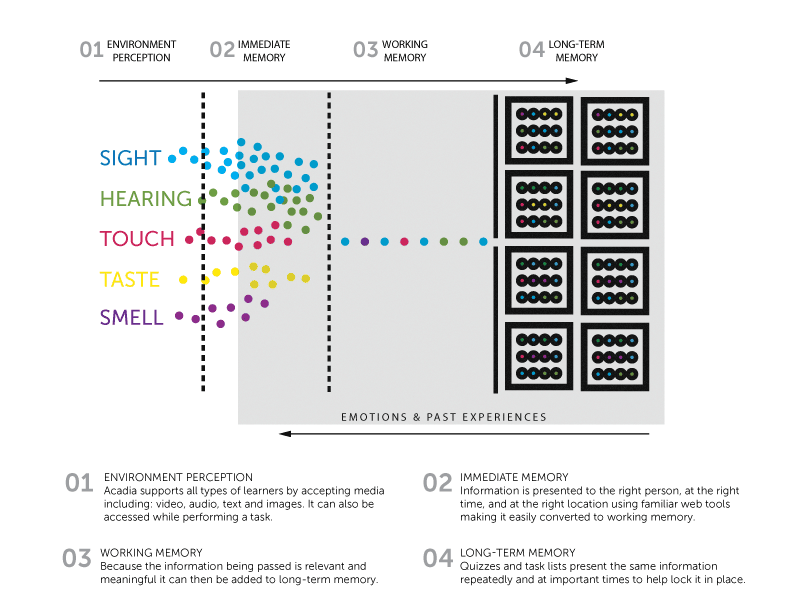

From the beginning, the fundamental nature of how the brain learns has served as the compass for developing the Acadia Performance Platform. Each phase of the memory process has been accounted for, and improvements have been made over time based on customer feedback.

All knowledge entered into the Acadia platform can be retrieved by employees using simple and intuitive online tools. Tools they are accustomed to using in their daily lives. This triggers emotions from past successful experiences and puts the employee in the proper mindset for learning.

All materials used in training (step-by-step instructions, images, video, etc.) can be added to policies, procedures and manuals in Acadia, making sure they are easily accessible while performing activities. By seeing these materials multiple times, it reinforces the correct behavior and helps to generate long-term memories.

Similarly, policies and procedures can be automatically converted to auditable task lists that employees can use on mobile devices while performing activities. With a consistent and structured approach to each important procedure, the one best way to perform it becomes adopted quickly and easily.

Assessing comprehension, through quizzing, after receiving training, performing a task, or acknowledging a policy can further help to engage long-term memory. It reinforces the most important material and helps make the employee accountable.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, employees can provide feedback on every document to suggest better, more efficient ways of performing tasks. Making an employee part of the process not only encourages a culture of continual improvement, it also helps them to think more critically about their work and makes each learning experience a positive one.

Sources:

- The World Is More Complex than It Used to Be

- Simplification of work

- History of employee engagement – from satisfaction to sustainability

- The Overwhelmed Employee: What HR Should Do?

- 4 Reasons Why Deploying A Learning Management System Is More Trouble Than It’s Worth

- How the brain learns 5th edition, David A. Sousa (p. 45-92)

Ready to crush your goals?

"*" indicates required fields